Berlin, the largest city of the German empire, the capital of the kingdom of Prussia.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 3

The images above are presented in a Jetpack Tiled Gallery block, set to the Circles style.

Berlin, the largest city of the German empire, the capital of the kingdom of Prussia.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 3

The images above are presented in a Jetpack Tiled Gallery block, set to the Circles style.

Yosemite National Park in California spans roughly 750,000 acres. It has been a UNSECO World Heritage Site since 1984.

The images above are displayed in a Jetpack Tiled Gallery block. The gallery block is contained within a Group block. The Group block is set to full width and has a dark background.

A chain of 26 atolls – lagoons encircled by coral reefs – in the Arabian Sea of the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is a tropical country, and its capital city is Malé.

This is a “Media & Text” block. It’s an easy way to create an attractive layout around an image.

This is a “Media & Text” block. It’s an easy way to create an attractive layout around an image.

This is a “Media & Text” block. It’s an easy way to create an attractive layout around an image.

This is a “Media & Text” block. It’s an easy way to create an attractive layout around an image.

The Covid19 pandemic has initiated a seismic shift in higher education that is part of a radical re-shaping of systems across the globe. While many within and around academia seem to be under the impression that this is a temporary change and a return to ‘normal’ will shortly ensue, there are good reasons to expect and prepare for an entirely new normal.

The Covid19 pandemic has initiated a seismic shift in higher education that is part of a radical re-shaping of systems across the globe. While many within and around academia seem to be under the impression that this is a temporary change and a return to ‘normal’ will shortly ensue, there are good reasons to expect and prepare for an entirely new normal.

The sudden large-scale move to remote instruction is forcing the question of value of educational entailments. Online education is sufficient, or at least this is the position that education institutions have to assert at this moment. Otherwise, they may have to be prepared to refund tuition for the last half the recent semester. In this assertion, however, is a tacit admission that much of what comes in an institution’s program ‘package’ is extraneous to the education itself. In the midst of what looks like a cascade of crises, in which the shackles of student debt are deeply entrenched, higher ed has some explaining to do. Regardless, at least for the moment, a great deal of elements deemed essential to higher education (such as physical classrooms and office buildings, for example) have been rendered superfluous. To be clear, the objective here is not to adjudicate which elements of higher education are superfluous and which are not. The simple objective is to point out that this adjudication process is undoubtedly underway as administrators face severe budget cuts and/or recognize the cost-saving benefits of eliminating legacy educational infrastructure.

Of course, settling for a sufficient education is underwhelming, and most will no doubt strive to be the best. Institutional brand and culture have been the primary tools of recruitment, and they have been built upon the material artifacts of geography, physical structures, and, yes, in-person real-life human beings. Students tour universities to get a ‘feel’ for the place, sizing up the football stadium, dormitories, and study halls while keeping an eye out for that superstar professor in their proverbial Gryffindor robes. Online learning has been around a while now, but, arguably, it has been primarily supplementary to the brick a mortar reality. The already crowded market for online learning is now super-saturated, at least momentarily, and should the elimination of legacy infrastructure take root, how will educational institutions create a viable and sustainable model in the new education order?

The way forward is a bit of an open question, but the current crisis has brought into full relief a couple of problems with some traditional education practices in the contemporary world. First, higher education seems to be increasingly fixed on information transfer as its primary mission, as diminished interest and investment in the more subjective areas such as the humanities attests. Professional development programs for faculty and emerging learning technologies seem to focus extensively on the best ways to engage students so that they encounter the ‘right’ information, store it effectively, and retain and retrieve it appropriately. That’s how one gets an A. If they can transfer this information from one context to another, they might even get an A+. Great emphasis has recently been put into active learning (gamification, for example) and high impact practices (research, internships, service learning, for example), but the utility of these seems to remain focused on finding the best approach to efficiently and effectively get the ‘right’ information into the student.

Information transfer is a questionable primary objective now because a student will likely encounter more information with their smartphone on the first page of a Google search than what they will retain from a full four-year degree. The assumption of this paradigm is that someone (aka the professor) knows what the ‘right’ information is that needs to be transferred, and that person polices successful/unsuccessful transmission/retrieval (read: learning) outcomes. This is a curator/gatekeeper approach to knowledge, and in an age of rapidly increasing and easily accessible information, a conduit can quickly become a bottleneck. In-person settings at least facilitate ancillary developmental components of interpersonal communication and relationship building, among other valuable things.

Another related problem is that if the information-transfer paradigm of education remains the primary focus there is a good chance that traditional institutions will find themselves awash in the saturated marketplace of online learning. The current crisis has prompted the need for educators to hastily convert traditional pedagogy into a remote world, and despite the best efforts of the undoubtedly well-intentioned, many have been thrown into an unfamiliar domain outside of their skill sets and comfort zones. Odds are that this situation will not produce the most competitive educational product. At least not fast enough. Traditional institutions suddenly have to compete in a domain already dominated by information giants, and without the accoutrements of the legacy infrastructure there is nothing for those giants to choke on. Why should one pay high tuition fees for a Zoom lecture if Lynda.com does a more effective job for a fraction of the cost? Should the present situation persist the result will be an ideal environment for the emergence of an Amazon of education, and while many may work towards that end and hope to be the ones on that trajectory, the stats of the matter are that they likely will not be. Like in any longtail enterprise, there will be only one Beyoncé. Only a few will make it big, and only the big will survive. Most will not.

One may point out that critical thinking is an important part of higher education, and this is surely a learning outcome cited in virtually all syllabi. However, one might argue that, given the fact that a student encounters this outcome in almost every course they take throughout their academic tenure, graduates should be downright experts in the practice. Either this expertise is not valued or not present as university graduates increasingly find themselves unemployed or underemployed upon completion of their program. While a worthy education objective, critical thinking is not likely the learning outcome that will save higher ed as digital education producers will no doubt find a way to tack this on to their course outcomes as well. This is not to dismiss this important function of higher education. This is only to suggest that it has not been effectively prioritized and/or made sufficiently visible so as to mark its value and become a bulwark against the ferocious appetite of the digital marketplace. Maybe this has simply been the result of poor marketing.

The goal here is not to paint a bleak picture just for the sake of it, and this analysis should in no way be interpreted as rooting for failure. Exactly the opposite is true. But, battening down the hatch of the old could very well be the seal of demise. In many ways the current crisis has been an opportunity to reflect on the aims of higher ed and chart the best way forward.

Traditionally, the role of higher education has been to cultivate engaged citizens, meet the needs of society and the economy, and try to explore questions of the world. All of these are still laudable and worthy of continued and even increased social and financial investments. The increasing complexity of the current era means that how these things are done needs to change, however.

To answer questions about the world there is a need for people with a diverse skill set capable of traversing multiple large knowledge domains. Covid19 is not simply a medical issue. It is a social-economic-biological-environmental-psychological (ad nauseam) issue. It is interdisciplinary. Information transfer alone will not suffice as answering questions about this issue requires one to be an effective information interface not merely an information repository in a single academic domain.

To address the needs of society and the economy there is a need for great agility as these are in constant and erratic flux. An army of contact tracers is needed at the moment, but a whole program or discipline is not necessary for that. Rather, there is a need to educate for adaptability and creativity, because who knows what jobs will be in demand next year or what innovative solutions will be required. The problems themselves are not yet apparent.

To encourage civic engagement is an objective needed now more than ever as the cascade of crises engulfs the globe, but peacemaking and worldview bridging are the current requisite skill sets. The big conflicts are no longer primarily between nation states. They are now rooted in local and virtual communities, and experts in creating common ground will surely be in high demand. This is perhaps one area where higher education can continue to shine and even increase its impact.

Humanity has spent eons mining the resources of the earth, but what if the new frontier was in fostering the knowledge, intelligence, and beauty of the human collective? What if the primary goal of higher education was to prioritize people over profits, cultivate the science of deep authentic relationships, to teach sophisticated tools of inclusion, collaboration and generative discourse? The power and ingenuity of the human spirit has already demonstrated its genius manifold, but it is jeopardized in a world reduced to mere information.

The one thing the information giants have not figured out yet is the art of human connection, and this era of social distancing has made this abundantly clear. People still need people. Meaning-making, narrative, care, ethics, love and similar ambiguous artifacts of the human condition are not yet subsumed in binary code, and so if higher education prioritizes these in its learning outcomes perhaps it has a really good shot at not only surviving, but thriving. Learn to build relationships, create and share stories, make meaning, work together, embrace difference and encourage diversity. If these exercises happen to involve learning to solve differential equations, so be it.

.

Trying to explain complexity theory is, well, complicated. It’s complicated because it is both a way of representing a world out there while at the same time constructing a world out there. What I mean is that there are complex systems in the world such as economies, the human body, and ant colonies, and these systems are relatively easy to see. They are made up of multiple interacting elements or agents, and they develop through local interactions that produce systemic patterns or emergent properties. At times, however, we can and do think of these systems as individual objects. I am immediately reminded of the glass sand-filled display cases with elaborate ant colony patterns garnering the awe and admiration of the young boys in whose rooms they inhabit. (Stereotypes dictate that the subject is a boy.) (And, yes. My own eyes are rolling too.)

Well, complexity is a way of describing such systems, but it’s also a way of seeing that can be applied to any object. As observers, we tend to look around and try to categorize and differentiate objects in the world, and so it’s rather normal to look at things and say: “This is complex and that is not.” For example, would we characterize a whiteboard marker as a complex system in the same way we would characterize an ant colony? Not usually, as it’s not as easy to see complexity in such a seemingly benign and inanimate object. While most would say no, I would argue that complexity is a way of looking and is not inherent in an object or phenomena. So, yes, a whiteboard marker can be characterized as a complex system as well.

The question then is not whether something is complex or not. The question is whether we apply a complexity lens or not. A simple whiteboard marker may appear to be an uncomplicated object. It’s a simple writing implement, from one point of view. From a complexity point of view, it is a set of atoms and molecules held together by technology designed by engineering intellectuals who are typically far removed both physically and socially from the manual labour required to extract the natural resources necessary to build this product and compile the requisite ingredients into said object. To the complexity-attuned observer, the marker simultaneously, through the presence of symbolic elements or ‘agents,’ conjures the emergent historical properties of civilization that sprang from the development of language and communication, laws and revolutions, and a variety of positive and not-so-positive human endeavors. We could look at how, traditionally, the ones who use the writing implement generally have more power than the ones constructing the implement. I could go on and on. Just as we can reduce the complexity of an ant colony to single display case, so too can we amplify the complexity of the simple inanimate whiteboard marker. Complexity is in the eye of the beholder.

Interdisciplinary Studies is the study of complexity. It is the process of developing and applying a complexity lens. Teaching interdisciplinarity is thus not about merely combining disciplines. That is a reductionist and ultimately impoverished conceptualization of this field. Teaching interdisciplinarity must be about cultivating the capacity to see complexity, understand complexity, and ultimately, impact complexity in ways that improve and empower our living realities.

In June of this year, I began teaching a six-week program at the Central Florida Reception Center as part of the Florida Prison Education Project. The course was entitled “Love and Faith, Family, and Friendships.” The plan was to cover the topic of love from multiple perspectives, which was typical of an interdisciplinary approach.

I approached this course with a great deal of trepidation. I did not know what to expect, but I was very pleasantly surprised. I had never even been inside a prison before, and I had (and still have) no idea what crimes the inmates committed or how long their sentences were. I did not ask, and they did not volunteer. For two hours per week, for six weeks, thirteen male inmates and I met to discuss love.

What surprised me the most was how engaged and motivated the students were to explore what probably appeared to be a rather superficial topic at first glance. The students read the material carefully. They respectfully challenged each other, and they respectfully challenged me. Should every class I teach be so enthusiastic I would be the happiest teacher ever. Indeed, in their final reflection, one student wrote, “I never thought that love was such a complex issue that we could talk about it for 6 weeks. I was wrong.”

The course syllabus stated: “This course on love has been designed to provide an interdisciplinary introduction to the concept of love. As such, it examines the philosophical, cultural, and religious influences on various concepts of love. Students will examine and analyze how these influences shape ideas and expectations of love in the contexts of faith, family, and friendships.”

The course objectives were:

In the first class, I introduced the Socratic Method in an abbreviated form: Question everything. For me, learning is more about getting good questions than getting true answers. I introduced the learning mindset (essentially, this is what is referred to Interdisciplinary Studies as “The Cognitive Toolkit”). The key elements of this mindset are open-mindedness, humility, intellectual courage, empathy, and curiosity. We went on to discuss common love tropes and their accuracy and relevance in different contexts. We discussed love as life, and how love can inspire us to open up and connect to others. We discussed love and social action (e.g., MLK and Gandhi), love and consumerism, love and language (how our language impacts not just what we think and understand, but how we act as well), among other things. Interestingly, we discussed romantic love very little in comparison. In many ways, it’s the least interesting concept in a culture super-saturated by the prominence of the love equals sex trope.

The unintended outcome of this course was much more significant than the intended ones. I did not explicitly state that one of the course outcomes would be increased open-mindedness. This outcome is always my hope, but I rarely see much progress among people in this regard (students or otherwise). In fact, blatant closed-mindedness of several people I love and care about has been a source of a great deal of discouragement and frustration as of late. These people are both smart and good yet closed to seeing the world in all its diverse glory. This class provided me with some much-needed hope.

Open-mindedness is not simply the willingness to listen to another’s perspective. It’s the willingness to be moved by another’s point of view. It is a willingness to be convinced, to change your mind if need be, or at the very least, to find value in one’s point of view even if (or especially if) you do not agree.

Open-mindedness entails empathy: People believe, see, and do things for a reason, and if we start with the premise that most people are good, we will be compelled to search beyond the surface for the goodness inherent in their perspectives. This, in my view, is the very heart and soul of learning.

Open-mindedness entails empathy, yes, but it also entails humility. I always explain humility as, simply, the willingness to be wrong. Sometimes, in Interdisciplinary Studies, we refer to this as an ignorance-based worldview. An ignorance-based worldview requires the conscious and intentional uptake of an intellectual position that acknowledges that regardless of what one thinks they know for sure, or how much one knows about a topic, there is always a chance that they could be wrong or at least learn more. This intentional intellectual move creates a gap between knowers and the known, and this gap is a space rich with potential for growth, both individually and collectively.

Such a worldview, I have argued, is the basis of love (at least a type of love) because in moving from conviction to maybe we allow ourselves to step into vulnerability, which is one place that is renowned for the facilitation of human connection. This move can be very difficult for men, however, because gender norms teach us that vulnerability equates to weakness, and weakness is dangerous and/or evil. It is definitely not masculine. Culture tells us that it should be staved off with violence, aggression, conquest, and/or possession. Yet, vulnerability is a crucial part of the human experience that we deprive men of when we stringently police masculinity with the policies of social norms and gender expectations. Beyond facilitating a broader capacity for learning, radical open-mindedness, including empathy and humility, might just be the one competency essential for addressing the compounding complexities of a world being torn apart by violent dogmatism and polarizing conflict-ridden politics.

According to the students, open-mindedness was indeed the most significant outcome. I really have no idea how this happened, as I just did what I always do. Here is what the students had to say:

“This class has been a game-changer for me. By that I mean how now I’m able to see things from many different angles. That has been my biggest take-away. A lot of times when I learn something I say “I know” then without thought I put limitations on myself and there is not more room for growth. With the topics discussed and how this class was conducted the methods learned here has changed how I approach people, conversations, how I argue/debate and so many areas. I would argue that courses like this one are essential not just for inmates but the world as tools to lay a solid foundation in our everyday lives for growth.”

“In the beginning, my mind was already made up. At this point, I’m not so sure. I’m not sure that I even like the uncertainty, but I am open to. I guess that’s the first step.”

“I have benefited from this class in that my eyes have been opened a little bit to the fact that I may not be right about some things and to leave some space in my mind to listen and learn from others.”

“I’ve enjoyed every minute of this class, not because it made me feel uncomfortable, but because it made me question some old concepts I’ve had. It also made me dig in a little deeper on others.”

“Thank-you for showing me how to accept-What if.”

The increase in open-mindedness as an outcome of this course was not just theoretical. It impacted how the students interacted with each other within the facility and beyond. This outcome was unintended, but I am thrilled. This was brought to my attention by one of the guards who was charged with accompanying me throughout the duration of my class. In front of the students, and again after they had left the room, the guard mentioned that she had noticed a difference in communication patterns and interactions.

In their own words:

“Come to find out, this six week program wasn’t entirely about love, and was more about developing critical thought…Here it is, week six, and I’ve put some of the ideas in this class to work and have been able to open or expand myself to other people’s ideas or thoughts. And, if you listen closely enough to what people are saying, you’ll find out that their point may be left in what they don’t say.”

“To my surprise, this class wasn’t solely about romantic relationships. This class implored us to incorporate love into all aspects of life. It taught me to identify some of the different types of love…but most importantly, it pushed me to think innovatively. To challenge my own thoughts. Why do I think this way?”

“I’m most appreciative because it’s had a positive effect on my relationship with my youngest daughter who always seems to argue with me about something at visitation. Well, she told me after our last visit that I seemed to have changed a little, not so steadfast in my opinions on things. I must thank you for that.”

To the extent that open-mindedness and human connection are part of my core values, I guess they are always intended outcomes of every interaction both in the classroom and beyond, but rarely do I see a direct impact. Usually, it’s some type of faith that propels my belief in and commitment to these values. I still do not really understand what happened here.

My experience with this course far exceeded my own expectations, and these men have had a profound impact on my life. Yeah, I always talk about this stuff, but it rarely gets this kind of reception. After every class, I came away feeling uplifted and edified. Although I did tell them directly, I am not sure if they truly grasped their positive impact on me. I have a renewed faith in humanity, and this is not an exaggeration by even a little. During their final presentations, their gratitude was overwhelming, and tears flowed amongst us. I am truly humbled and grateful for this opportunity. I do not know what they have done, and I don’t want to know. All I can say is that for two hours a week, for six weeks, all thirteen men in this class did good in the world. That’s all I ask of anyone.

I don’t usually talk about my own beliefs, and a big reason for this is that I try very hard to remain open-minded. This means that my beliefs are consistently subject to review and revision. This being said, we are living in a polarized era where one is quickly branded as either for-or-against an idea or belief system, often based on some arbitrary observation, and if one agrees on one thing, it is often assumed that they will fall in line with a constellations of beliefs and positions that are assumed to be inextricably related. This, in my opinion, is highly problematic. Many of our beliefs range across a spectrum of positions and are often more individualized than we assume. Get to know people and resist the urge to simply branding them one way or another, I would suggest.

I know many of us feel that this state of affairs is new and unique to our era, but I also think that this is not true. May I remind you of the Montagues and the Capulets? Polarization is nothing new. What is new, however, are the platforms through which we can communicate, and while many bemoan the impact of social media and open access to information as the vehicles through which we fortify our silos and hedge our ideologies, I see these developments differently. I recognize their pitfalls, but I also see these platforms as potentially rich resources for building common ground and bridging seemingly impossible divides.

Why am I saying all this? At the risk of causing friction with some of my non-believing friends, I want to make a point: one does not need to believe in Christianity per se to believe in good Christians. To me, beliefs are far less relevant than actions, and relationships are far more important than dogma. It is no secret that I grew up in Christianity and that many of my family and friends are Christians. I am not willing to sacrifice these relationships over questions of faith and belief. Furthermore, I also have a lot of great friends and family that belong to various secular communities, and the same is true in this case. I often find myself at odds with their beliefs as well, but am not willing to prioritize ideological positions over people.

My philosophy of life is simple: I want to do good in the world, and I want to build and maintain relationships with people who share a similar objective. What “good in the world” means is different to different people, but I have found that I can always find common ground with those that share this same orientation regardless of their personal beliefs or lack thereof. At the risk of sounding religious, one might label this philosophy as “love.” Perhaps this is the one ‘dogma’ to which cling.

So, I haven’t done a great job keeping up with my writing plans for the year, but this falls in line with all of our New Year’s goals generally speaking. That being said, I saved some money and lost 50 pounds, but the writing? It’s killing me.

Although I haven’t kept my reading journal up, I have managed to get through a number of interesting books. The best one I’ve read so far was Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari. This book was recommend to me by my brother, but it took me a while to get around to reading it. When I finally did, however, I could hardly stop, and when I finished, I was filled with the overwhelming sense that I need not worry about writing because everything has already been said. Of particular note were the questions of the status and future of science and technology. The path is somewhat ominous, but not without hope of pushing humanity towards a more humane technological future.

After reading this book, I immediately went to Harari’s first book: Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. This one was good too, but I find it difficult to keep my mind engaged with the finer details of evolution, and so I was more prone to search for the nuggets of insight in this book. There are lots. Looking at human evolution in terms of revolutions–the cognitive revolution, the agricultural revolution, the fomenting of religion and politics, and the scientific revolution–Harari challenges the underpinnings of human society from its roots to its current multivalent branches. A masterpiece in the investigation of the underside of ‘normal’, this book is the epitome of interdisciplinary integration.

In no particular order, my reading list since the start of the year has also included the following titles:

Utopia for Realists: How We Can Build the Ideal World by Rutger Bregman. This book has gotten much press since Bregman’s appearance at Davos where he challenged the taxpaying habits (or lack thereof) of the billionaires seeking to improve the world. Taxes are the single best route to broad-scale improvement, he argues. His book elucidates the arguments and potential benefits of a universal basic income in an inspiring, if somewhat rose-colored glasses-like.

Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman was somewhat dry throughout as he related insights from his long career in cognitive science. What was fascinating, however, is the extent to which we as human have such little control over our decision making. Even though I kind of knew this, the impact of this insight has yet to be grappled with to any real extent, either individually or as a society.

The Art of Non-Conformity: Set Your Own Rules, Live the Life You Want, and Change the World by Chris Guillebeau was an absolute blast. In fact, I am thinking of assigning this book to my students. It’s not an incredibly academic text, but the practical wisdom is clear, concise, and entirely actionable. I love to assign books that give ideas to chew on rather than claim to espouse truths about the world. All the things I talk about are in here, and can be contextualized nicely within Interdisciplinary Studies.

All the Single Ladies: Unmarried Women and the Rise of an Independent Nation by Rebecca Traister was a gift from a friend. I read this with rapt attention as I prepared and delivered a talk a the National Organization for Women’s Florida State Conference. My talk was on radical sexuality, or the need to call out what I see as a re-inscription of regressive gender and sexual politics in the potentially revolutionary #MeToo movement. I loved this book even while somewhat disappointed in the dampened radicalness of its timbre.

This works out to be a bit more than one book per month. Perhaps I could up the pace a bit, but this is what’s comfortable. It works out to about an hour of reading a day, but that doesn’t include the journal articles, online articles, etcetera. The trick is to turn my interaction with all of this into a piece of written work that conveys my own insights, but I am finding this so very challenging. I sit in front of the screen with a plan in mind yet a lack of words to execute my thoughts. I don’t know why I am finding this to be such a struggle.

Part of the problem has to do with the act of composition itself. As soon as I beginning to write, I think of where my thoughts are coming from, or the sources to which they’re connected, in other words. This is the same problem I have with writing music. Every time I start to compose I am reminded of another familiar song. I do not feel authentic. Is it simply a lack of confidence? Perhaps, but I think there’s more to it. I think writing is a social thing, and I simply need more interaction with others. Not just through books, but through conversation, the sharing of ideas, and challenges.

What’s next on my reading list? Here’s what I have in mind:

Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger, by Rebecca Traister

This is all I have for now. Suggestions are very welcome.

I forgot one! The first one I read this year…The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. I know this is a classic, but I had never read it. I still don’t really get it, but it’s in the bag. Confession: I do read in a classic sense. Like with a book in my hand or my tablet and Kindle; however, I have discovered a secret. Well, it’s not that much of a secret really, but it’s audiobooks. I workout a fair bit, having lost @50 pounds the past year (did I mention…? 😉 ), and so my workout time has become somewhat sacred. I am using Scribd, an app that has numerous print-ish books and often the corresponding audiobook. I love this option. I typically listen to the audiobook at 1.5 or 2 times the regular speed, and if there’s something I want to re-visit or study more in-depth I turn to the written text. I think I’m paying 9$ a month for my subscription. Worth every penny so far!

I do read a fair bit, though not nearly as much as I used to. I think this is true for many people. Of course, I watch a lot of YouTube videos about a wide range of things, but I’m not sure how well any of this gets lodged into my memory. While reading affords the luxury of time to contemplate ideas and respond to the author’s arguments, the passive nature of videos requires some form of extravagant stimuli to ensure retention. In general, however, I have a terrible time remembering what I’ve read or watched. I sometimes wonder what the point of reading is if I never remember any of the key ideas. Are there benefits to be gained from the reading process itself, even without retention? I am not sure, but I do know that I’d like to remember more regardless.

So, I’ve decided to try and keep a more formal record of what I read/watch to see if that helps. The first book I finished was a novel by Carl Hiaasen. He is a Florida author, and the story is about the politics of bass fishing in Florida. Although I had not heard of this author, apparently he is rather well-known for his rich characters and outlandish plot twists that seem not so outlandish when contextualized as a Floridian storyline. While I found the story to drag on a bit towards the end, I will read a few more selections from this author.

The first book I finished was a novel by Carl Hiaasen. He is a Florida author, and the story is about the politics of bass fishing in Florida. Although I had not heard of this author, apparently he is rather well-known for his rich characters and outlandish plot twists that seem not so outlandish when contextualized as a Floridian storyline. While I found the story to drag on a bit towards the end, I will read a few more selections from this author.

One of the more colorful characters in this novel is a televangelist named Charles Weeb. He is first and foremost a businessman (though not a great one). The underlying mockery of religious phonies highlights the maliciousness of the exploitation of religious belief for monetary gain, and this element of the story was familiar yet still poignant.

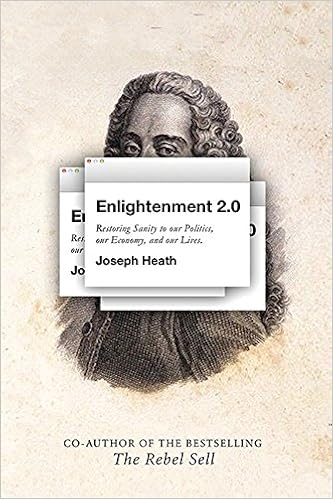

The next book I’m working on, Enlightenment 2.0, is by Joseph Heath. This book chronicles the evolutionary history of the development of reason and argues for a new understanding of rationality that encompasses not just individual knowers, but networks of others and artifacts that scaffold individual rationality and compensate for the tendency to exploit cognitive shortcuts that have facilitated our evolutionary successes.

The next book I’m working on, Enlightenment 2.0, is by Joseph Heath. This book chronicles the evolutionary history of the development of reason and argues for a new understanding of rationality that encompasses not just individual knowers, but networks of others and artifacts that scaffold individual rationality and compensate for the tendency to exploit cognitive shortcuts that have facilitated our evolutionary successes.

Chapter 1: The calm passion-Reason: its nature, origin, and causes

Our brains have evolved to solve problems as economically and efficiently as possible, according to this author: “Our brain is more like a bureaucracy or a customer service center, which strives to solve every problem at the lowest possible level” (Kindle Locations 474-475). This is not always the most effective, however, as expediency often comes at the expense of investing in the cognitive work necessary to develop the capacity to solve more complex and sophisticated problems. “Thinking rationally is difficult, which is why most of us try to avoid doing it until absolutely forced” (Kindle Locations 523-524). Of importance in this chapter is the introduction of what the author refers to as two systems of cognition: intuitive, heuristic and rational, analytic. This is reminiscent of another book that I have on my reading list: Thinking Fast and Slow, by Kahneman. We’ll come back to this book later.

The thrust of this chapter is that evolution has endowed humans with a variety of cognitive shortcuts to enable survival, but cognition has been assembled piecemeal in response to survival challenges. It was not intentionally moving towards rationality, and in fact, rationality seems to be an exaptation (the byproduct of other adaptations). “Thus the way that your brain feels after writing an exam is like the way your back feels after a long day spent lifting boxes—neither was designed for the task that it is being asked to perform. This is of enormous importance when it comes to updating the ideals of the Enlightenment. Reason is not natural; it is profoundly unnatural.” (Kindle Locations 827-830).

This reminds me of a TedTalk that I regularly show in my class. I agree that rational thinking can be difficult and uncomfortable, but I never really get this conceptual divide between “natural” and “unnatural”. Unless one assumes that there is something beyond or outside of the natural, this conceptualization makes little sense.

Bottom line from this chapter: thinking is hard because evolution is/was lazy.

Interdisciplinary Studies is about creativity, at least that’s the claim, but where is this creativity exercised? In choosing one’s career path? In choosing one’s compilation of courses? Or, as I hope to suggest is the most significant place, in the daily academic practices of interdisciplinarians?

Interdisciplinary Studies is about creativity, at least that’s the claim, but where is this creativity exercised? In choosing one’s career path? In choosing one’s compilation of courses? Or, as I hope to suggest is the most significant place, in the daily academic practices of interdisciplinarians?

In the Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies textbook that I and others use in our Cornerstone class, the authors write that “in interdisciplinary work, creativity involves bringing different perspectives and previously unrelated ideas, discovering commonalities among them, and combining them into a more comprehensive understanding” (21). I disagree with the quantitative component of this statement because often creative pursuits are about knowing differently not necessarily more, nonetheless the centrality of creativity is key. I have been working very hard to cultivate a creative classroom, and I’ve had varrying degrees of success.

Creativity is not easy to teach, it turns out. Indeed, according to Bloom’s taxonomy, it’s at the very top of the pedagogical pyramid. I have to admit that I’ve been struggling a bit with getting students to lighten up and delve into the quirky and whimsical dimensions of intellectual work. But that’s likely because the concept of quirky whimsical intellectual work strikes them as an oxymoron. Academia is serious stuff. GPAs are on the line. What’s so quirky and whimsical about that? When provided with prompts to explore unconventional ways of thinking, they often either stare at me with blank expressions or challenge my intellectual forays by reiterating conventional tropes in regards to whatever topic is on tap. Not only is there often a lack of capacity for creative thinking, there is a lack of enthusiasm about even the prospect of it. Why?

Creativity is not easy to teach, it turns out. Indeed, according to Bloom’s taxonomy, it’s at the very top of the pedagogical pyramid. I have to admit that I’ve been struggling a bit with getting students to lighten up and delve into the quirky and whimsical dimensions of intellectual work. But that’s likely because the concept of quirky whimsical intellectual work strikes them as an oxymoron. Academia is serious stuff. GPAs are on the line. What’s so quirky and whimsical about that? When provided with prompts to explore unconventional ways of thinking, they often either stare at me with blank expressions or challenge my intellectual forays by reiterating conventional tropes in regards to whatever topic is on tap. Not only is there often a lack of capacity for creative thinking, there is a lack of enthusiasm about even the prospect of it. Why?

Perhaps because it’s difficult? I don’t think this is a good answer. Many of my students are running academic marathons of sorts, trying to get through while juggling huge course loads, working, managing family, navigating institutional complexities, and facing a volatile political climate and an uncertain future. If anyone can handle difficult tasks, it’s my students. By and large, they are no strangers to hard work. I don’t think this is the best answer.

A better answer, I think, is more pernicious, in some ways. Remember Sir Ken Robinson? He has argued to more than 44 million people that school, in its industrial formulation, kills creativity, and he has convinced me. He argues that creativity is as important as literacy and should be treated with the same status, but I don’t think this message has made it through to higher education.

I had career services come to my class this semester to speak to my students. The title of their talk is “Majoring in Happiness.” During this talk, the speaker passed out pamphlets with a short survey that allowed students to assess their own personalities and intellectual orientations. The back page of the pamphlet provides an interpretation of the survey, and test-takers can fall into one or more of the following categories: “Realistic Majors” (doers), “Investigative Majors” (thinkers), “Artistic Majors” (creators), “Social Majors” (helpers), “Enterprising Majors” (persuaders), or “Conventional Majors” (organizers). The bulk of my students were either “Investigative Majors” or “Social Majors.” Both of these categories are firmly ensconced in the realm of certainty–true/false, and right/wrong. Virtually no one identified themselves as creators. I don’t think we are really witnessing personality results but rather education results that teach ‘right’ answers and solvable problems. If IDS is truly about creativity, and I believe it is, we have our work cut out for us.

As an instructor in IDS, I do not believe that my task is really about teaching content (I am sorry to offend the textbook writers and their ilk). There are a few key concepts and ideas that would be helpful for students to know, but let’s be honest, it’s not exactly rocket science. My task, as I see it, is much more difficult. It is to inspire students to be different, and to create a space where intellectual experimentation is fostered and rewarded. We need to provide creativity tools that students can apply throughout their whole learning experience setting the stage for application to their careers and lives in general. We need to teach creativity, or to unlearn conformity, to be more to the point.

Apart from classroom pedagogy, I think there is some important institutional work that must be done by IDS programs as well. IDS as a creative intellectual endeavor, despite its growth over the past couple decades, continues to face stigma. The world is changing and creativity practitioners are more and more in demand. This puts IDS on the cutting edge, as graduates from these programs are showing us and the world. Changing hearts and minds is never an easy task, but perhaps there are things that can be done. Increasing the profile of IDS majors and practitioners, for example. Engaging in campus conversations and building relationships across disciplines and throughout various communities on campus and beyond are certainly ways to strengthen IDS programs and provide support for our students taking classes in disciplinary department. But, it has to start in the classroom with individual instructors teaching in creative communities of practice, or in classroom communities practicing creativity, more precisely.